zk-SNARKS Under the Hood - How They Work

In this post, I’ll take you on a journey to demystify zk-SNARKs – one of the most fascinating cryptographic innovations powering privacy and scalability in the blockchain ecosystem. As someone deeply interested in this technology myself, I want to share what I’ve learned about how these “zero-knowledge proofs” actually work beneath the surface.

Table of contents

- What is a zk-SNARK

- Non-Interactive Zero-Knowledge of a Polynomial

What is a zk-SNARK?

zk-SNARK stands for Zero-Knowledge Succinct Non-interactive ARgument of Knowledge. That’s quite a mouthful, so let’s break it down:

- Zero-Knowledge: Proves knowledge of information without revealing the information itself

- Succinct: Proofs are small and quick to verify

- Non-interactive: No back-and-forth communication needed after initial setup

- Argument of Knowledge: Cryptographically secure proof that the prover possesses specific information

At its core, a zk-SNARK allows Alice to prove to Bob that she knows a secret value without telling Bob what that value is. Bob can verify the proof’s validity with mathematical certainty.

Real-World Applications

Before diving into the technical details, let’s explore some concrete examples of what zk-SNARKs enable:

- Private Transactions: Prove you sent a valid payment without revealing the amount or recipient

- Identity Verification: Prove you’re over 21 without showing your actual birthdate

- Tax Compliance: Prove you paid sufficient taxes without exposing your entire financial history

- Supply Chain: Verify ethical sourcing without revealing proprietary supplier information

- Voting Systems: Prove your vote was counted without revealing who you voted for

The Players: Prover and Verifier

The zk-SNARK protocol involves two primary participants:

- The Prover: Has some secret information and wants to convince others of a statement about that information

- The Verifier: Wants to confirm the statement is true without learning the secret information

For example, imagine the Prover wants to demonstrate: “I have more than 10,000 Euros in my bank account” without revealing the exact balance. The zk-SNARK allows the Verifier to be mathematically convinced of this statement’s truth without seeing any bank details.

The Three Essential Properties

For a zk-SNARK protocol to be valid and useful, it must satisfy three critical properties:

- Completeness: If the statement is true and the Prover follows the protocol honestly, the Verifier will be convinced with overwhelming probability.

- Soundness: If the statement is false, no dishonest Prover can trick the Verifier into accepting the proof, except with negligible probability.

- Zero-Knowledge: The Verifier learns absolutely nothing about the underlying secret information beyond the validity of the statement being proven.

Polynomial Equations recap

I am sure that most of you learned about polynomial equations in school. Since polynomials form the mathematical backbone of many cryptographic systems, let’s recap some of their key properties:

- The degree of a polynomial is determined by its greatest exponent, in case for $f(x)$, then the exponent of $x$. For example: $f(x) = x^3 - 6x^2 + 11x - 6 $ -> greatest exponent is $3$, so the degree of the polynomial is $3$.

- Two distinct polynomials of degree most $d$ can intersect at no more than $d$ points (intersection $f(x) = g(x)$).

If a prover claims to know a polynomial, the verifier can easily verify that the prover indeed knows it, by

- Choosing a random value for $x$ and calculating $f(x)$ locally

- Asking the prover to calculate $f(x)$ for the same value of $x$ and return the result

- Verify that local calculation matches the prover’s result.

We might ask ourselves: what are the chances that the prover could cheat by “accidentally” providing the correct value of $f(x)$ without actually knowing the polynomial?

The answer is: the probability is negligibly small.

Consider a field with range for x from $1$ to $10^{77}$. If the prover knows a different polynomial $g(x)$ of the same degree, then $f(x)$ and $g(x)$ can agree in at most $d$ points (where $d$ is the degree). Therefore, the number of points where evaluations differ is at least $10^{77} - d$. The probability that a randomly chosen $x$ accidentally “hits” any of the $d$ shared points is at most $d / 10^{77}$, which is negligible for practical values of $d$.

The number of points where evaluations are different is $10^{77} - d$ (where $d$ number of intersections). Henceforth the probability that $x$ accidentally ‘hits’ any of the $d$ shared points is equal to $d / 10^{77}$, which is negligible.

This polynomial verification protocol:

- Requires only 1 round of communication

- Provides overwhelming probability of detecting a cheating prover

- Serves as a foundational building block for zk-SNARKs

This polynomial commitment and verification technique is one of the reasons why polynomials are at the core of zk-SNARKs and many other cryptographic protocols.

Non-Interactive Zero-Knowledge of a Polynomial

Proving Knowledge of a Polynomial

In the previous section we introduced a protocol, which allows a prover to prove knowledge of a polynomial. But it is important to note that the protocol is based on a weak notion of proof, since the protocol does not enforce the prover to know a polynomial. The prover can use any means available to him to come up with a correct result. Another problem is if the possible range of values for the polynomial is small, the prover can simply guess the polynomial and the probability that it is going to be accepted is non-negligible anymore, which is not good.

Therefore, will we have to address those issues. But before that, let’s take a look at what it actually means to know a polynomial.

What does it mean to know a polynomial?

Most of the time you will see polynomials expressed in the form of: \(c_n*x^n + ... + c_1*x^1 + c_0*x^0\) where $c_n$ is the coefficient of the polynomial, $x$ is the variable, and $n$ is the degree of the polynomial. If someone claims to know a polynomial, what they really know is the coefficients of the polynomial.

For example if a prover claims to know a polynomial of degree 3, such that $x = 1$ and $x = 2$ they could know \(x^3 − 3*x^2 + 2*x = 0\). For $x = 1$ we get $1 − 9 + 2 = 0$ and for $x = 2$ we get $8 − 12 + 4 = 0$.

You might be wondering how we got the mentioned polynomial for $x = 1$ and $x = 2$: factorization.

The Fundamental Theorem of Algebra states that any polynomial can be factored into linear polynomials (a degree 1 polynomials representing a line), as long it is solvable. Which means that we can express any valid polynomial as a product of its factors:

\[(x - a_0) * (x - a_1) * ... * (x - a_n) = 0\]In the case where the prover might know \(x^3 − 3*x^2 + 2*x = 0\), we assume that the third solution is $x = 0$: \((x - 1) * (x - 2) * (x - 0) = 0 => x^3 - 3x^2 + 2x = 0\)

Coming back to our example where a prover claims to know a polynomial of degree 3, such that $x = 1$ and $x = 2$, we can express it as:

\[(x - 1) * (x - 2) * (x - a_0) = 0\]Where $a_0$ is the third root of the polynomial.

Now, if a prover wants to prove that he knows a polynomial of degree 3, such that $x = 1$ and $x = 2$ without disclosing the polynomial itself, he needs to prove that his polynomial is the multiplication of the cofactors $t(x) = (x - 1)(x - 2)$ and some arbitrary polynomial $h(x)$, i.e.: \(p(x) = t(x) * h(x)\)

Where $h(x)$ is equal to $x - 0$ in our example.

How does the prover prover that he knows the $p(x)$ polynomial without disclosing it?

By division without a remainder: \(h(x) + r(x) = \frac{p(x)}{t(x)}\) where $r(x) = 0$ since the requirement is ‘division without a remainder’.

In our example \(h(x) = \frac{(x^3 - 3x^2 + 2x)}{((x - 1)(x - 2))}\) \(h(x) = x\) and the remainder is $0$.

The prover can prove that he knows the polynomial $p(x)$ by proving that the division of $p(x)$ by $t(x)$ has no remainder.

Putting this together into a protocol:

- Verifier samples a random value $r$, calculates $t = t(r)$ and gives $r$ to the prover

- Prover calculates $h(x) = p(x) / t(x)$ and evaluates $p(r)$ and $h(r)$; the resulting values $p$, $h$ are provided to the verifier

- Verifier checks that $p(r) = t(r) * h(r)$ and accepts the proof if the equality holds

Let’s see how this protocol works with $p(x) = x^3 − 3x^2 + 2x$ and $t(x) = (x - 1)(x - 2)$.

- Verifier samples r random value $23$, calculates $t = t(23) = (23 - 1)(23 - 2) = 462$ and gives $r = 23$ to the prover

- Prover calculates $h(x) = p(x) / t(x) = x$, evaluates $p = p(23) = 10626$ and $h = h(23) = 23$ and provide $p, h$ to the verifier

- Verifier then checks that $p = t * h: 10626 = 462 * 23$, which is true, so the verifier accepts the proof.

If the prover uses a different polynomial $p’(x) = 2x^3 - 3x^2 + 2x$, then the prover gets $h(x) = p’(x) / t(x) = 2x + 3 + 7x - 6$, were $7x - 6$ is the remainder of the division $p(x) / t(x)$. Since

\(\begin{aligned} p(x) &= t(x) * h(x) + r(x)\ (\because r(x) \neq 0)\\ p(x) &= t(x) * h(x) + r(x) \\ \frac{p(x)}{t(x)} &= h(x) + \frac{r(x)}{t(x)} \\ \frac{p(x)}{t(x)} - \frac{r(x)}{t(x)} &= h(x) \\ h(x) &= \frac{p(x)}{t(x)} - \frac{r(x)}{t(x)} \\ h(x) &= 2x + 3 + \frac{7x - 6}{t(x)} \\ \end{aligned}\) the prover will have to divide the remainder by $t(r)$ in order to evaluate $h(r)$.

Due to the random selection of $r$ by the verifier, there is a low probability that the evaluation of the remainder will be evenly divisible by $t(x)$. To catch the cases where it is not evenly divisible, the verifier will have to additionally check that $p(r)$ and $h(r)$ are integers. In case they are not integers, the verifier will reject the proof.

Example: \(h(23) = (2×23 + 3) + (7×23 - 6)/t(23) \\ h(23) = 49 + 155/462 \\ h(23) = 49 + 0.3355 \\\) $h(23)$ is not an integer, so the verifier rejects the proof.

But this puts a constraint on the allowed polynomials, since the coefficients of the polynomial must be integers. If the coefficients are not integers, the verifier has no way of distinguishing a valid polynomial from an invalid one?

That’s why we are going to introduce cryptographic primitives, where such division does not exist. You will soon understand why.

Remarks:

Now we (as verifier) can check a polynomial for specific properties without learning the polynomial itself, so this already gives us some form of zero-knowledge and succinctness.

Nonetheless, there are multiple issues with this construction:

- Prover may not know the claimed polynomial $p(x)$ at all. He can calculate $t = t(r)$, select a random number $h$ and set $p = t * h$, which will be accepted by the verifier as valid, since the equation holds.

- Because prover knows the random point $x = r$, he can construct any polynomial which has one shared point at $r$ with $t(r) * h(r)$.

- In the original statement, prover claims to know a polynomial of a particular degree. In the current protocol there is no enforcement of degree. Hence prover can cheat by using a polynomial of higher degree which also satisfies the cofactors check.

Let’s dig a bit deeper why these even exist.

Issue 1: Prover may not know the claimed polynomial $p(x)$ at all

At the beginning of the section, we have the following statement:

For example if a prover claims to know a polynomial of degree 3, such that

x = 1andx = 2…

and

The Fundamental Theorem of Algebra states that any polynomial can be factored into linear polynomials (a degree 1 polynomials representing a line), as long it is solvable. Which means that we can express any valid polynomial as a product of its factors:

(x - a_0) * (x - a_1) * ... * (x - a_n) = 0

I guess it is rather easy to spot, that the prover can simply select any random $h$ and set $p(x) = t(x) * h(x)$.

Issue 2: Prover can construct any polynomial which has one shared point at $r$ with $t(r) * h(r)$

The prover can come up with a polynomial $p’(x)$, such that $p’(r) = t(r) * h(r)$ without knowing the polynomial $p(x)$.

After receiving the value $r$, the prover comes up with a polynomial $p’(x)$, calculates $p’(r)$, and then calculates $h’(r) = p’(r) / t(r)$. The prover then sends $p’(r)$ and $h’(r)$ to the verifier, which will accept the proof.

Issue 3: No enforcement of degree

There is no enforcement of degree in the protocol. The prover can use a polynomial of higher degree which also satisfies the cofactors check. For example, if the prover claims to know a polynomial of degree 3, such that $x = 1$ and $x = 2$, he can use a polynomial of degree 4 or higher which also satisfies the cofactors check. For example, the prover can use $p’(x) = (x - 1)(x - 2)(x - 3)(x - 4)$ which is of degree 4 and also satisfies the cofactors check. The verifier has no way of knowing the degree of the polynomial used by the prover.

How do we address these issues?

To address these issues, we need to introduce cryptographic primitives. Issues 1 and Issue 2 are possible, because the values are presented in cleartext, prover knows $r$ and $t(r)$. To resolve those issues, we are going to use a cryptographic primitive that allows us to perform calculations on hidden values, namely homomorphic encryption.

Let’s get to it.

Homomorphic Encryption

Homomorphic encryption allows to encrypt a value and perform operations on the encrypted value without revealing it.

We are going to introduce a simple homomorphic encryption scheme, which allows us to perform addition and multiplication on encrypted values.

Simple Homomorphic Encryption Scheme

The general idea is that we choose a base natural number $g$, e.g. $g=5$ (the requirements for that number are out of scope for this post) and to encrypt a value $v$, we exponentiate $g$ to the power of $v$:

\[Enc(v) = g^v\]If we would like to encrypt the value $v=3$, we would get:

\(Enc(3) = 5^3 = 125\) 125 is the encrypted value of $3$. If we want to multiply this encrypted value by $2$, we raise the encrypted value to the power of $2$:

\[Enc(3)^2 = (5^3)^2 = 5^{3*2} = 5^6\]What does that mean: We just multiplied an unknown value (here $3$) by $2$, without decrypting it.

We can also perform addition, by through multiplication. Let’s say we want to add $2$ to our secret value $3$: \(Enc(3) * Enc(2) = 5^3 * 5^2 = 5^{3+2} = 5^5\)

And we can also do subtraction, by dividing the encrypted values:

\[Enc(3) / Enc(2) = 5^3 / 5^2 = 5^{3+2} = 5^1\]One problem: The base $g=5$ is public and it is easy to brute-force small values. To address this, we are going to perform the exponentiation in a finite field using modular arithmetic. In case you forgot, we are going to give a brief refresher on modular arithmetic.

Modular Arithmetic Refresher

Modular arithmetic is a system of arithmetic for integers, where numbers “wrap around” upon reaching a certain value, called the modulus.

For example, in modulo $7$ arithmetic, the numbers wrap around after reaching $7$. So, $7 \mod 7$ is $0$, $8 \mod 7$ is $1$, $9 \mod 7$ is $2$, $15 \mod 7$ is $1$, and so on. It also works for negative numbers: $-1 \mod 7$ is $6$, $-2 \mod 7$ is $5$, etc.

We can perform addition, subtraction, and multiplication in modular arithmetic as follows:

- Addition: $(a + b) \mod m$

- Example: $(5 + 4) \mod 7 = 2$ (since $9 \mod 7 = 2$)

- Subtraction: $(a - b) \mod m$

- Example: $(5 - 4) \mod 7 = 1$ (since $1 \mod 7 = 1$)

- Multiplication: $(a * b) \mod m$

- Example: $(5 * 4) \mod 7 = 6$ (since $20 \mod 7 = 6$)

- Exponentiation: $(a^b) \mod m$

- Example: $(5^3) \mod 7 = 6$ (since $125 \mod 7 = 6$)

Were $a$ and $b$ are integers, and $m$ is the modulus. It is important to note that the order of operations does not matter, e.g. we can perform addition before or after taking the modulus.

Why is modular arithmetic helpful in our case?

It turns out that if ew use modular arithmetic, having a result of an operation, it is non-trivial to go back to the original numbers because many different pairs of numbers can produce the same result when taken modulo m.

Without the modulus, it is easy to determine the original numbers from the result.

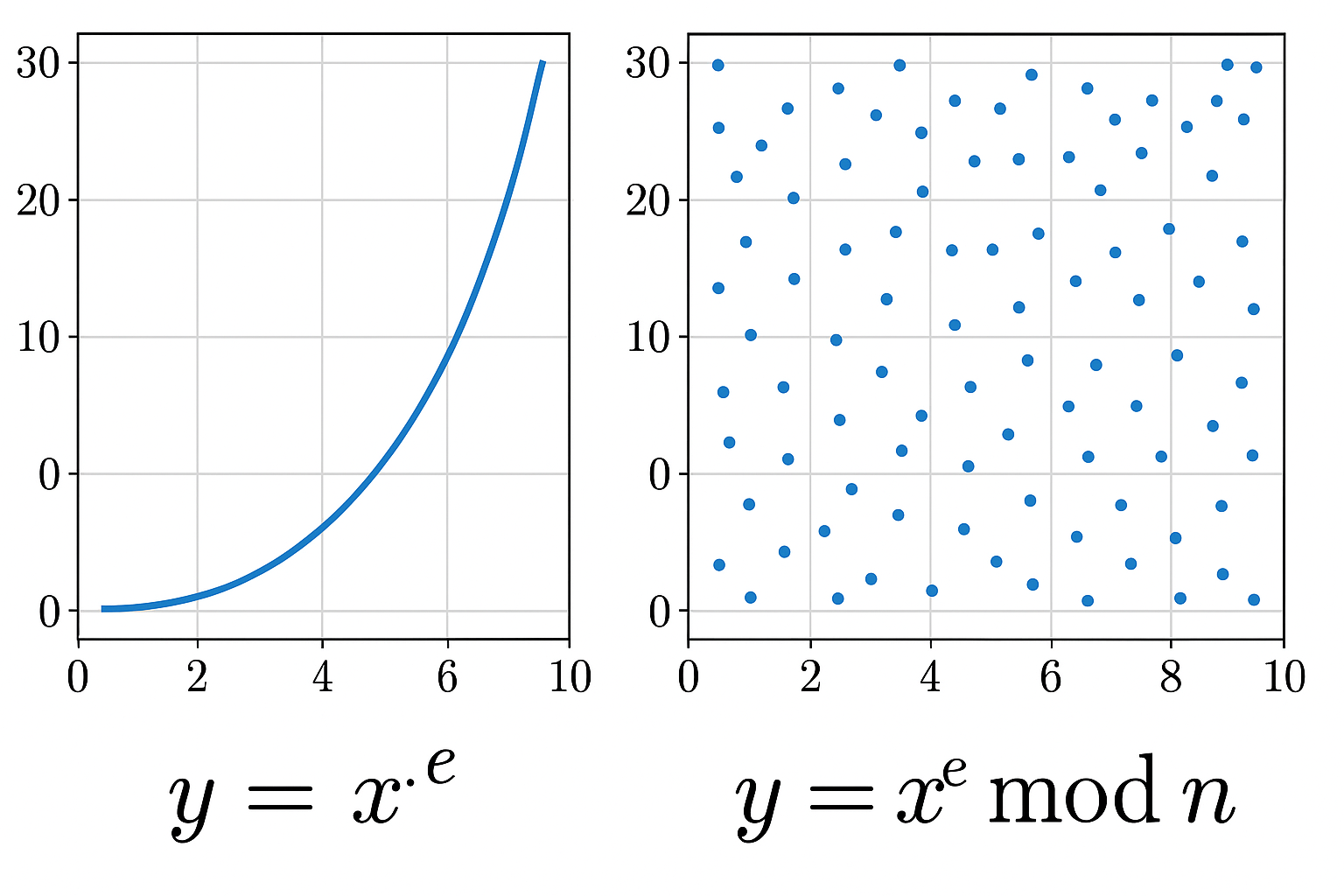

Let’s see how this looks graphically for RSA encryption. RSA has the following formula for encryption and decryption:

\[\begin{aligned} \text{Encryption: } c &\equiv m^e \ (\text{mod}\ n)\\ \text{Decryption: } m &\equiv c^d \ (\text{mod}\ n)\\ \end{aligned}\]Where m is the plaintext message, c is the ciphertext, e is the public exponent, d is the private exponent, and n is the modulus.

But let’s see how it would look like without the modulus:

\[\begin{aligned} \text{Encryption: } c &\equiv m^e \\ \text{Decryption: } m &\equiv c^d \\ \end{aligned}\]Here a graphical representation of RSA encryption without and with modulus:

On the left side you can see the smooth curve of the function y = x^e (encryption), and on the right side you can see the scatter plot of the function y = x^e mod n (encryption with modulus). The smooth curve illustrates the clear relationship between x and y, making it easy to determine the original value of x from y.

By adding the modulus, we get this “cloud of dots” on the right side, destroying the smoothness of the curve and making it difficult to determine the original value of x from y.

Homomorphic Encryption with Modular Arithmetic

Let’s revisit our simple homomorphic encryption scheme, but this time using modular arithmetic.

\[Enc(v) = g^v \ (\text{mod}\ p)\]Here some examples of operations on encrypted values using modular arithmetic:

\[\begin{aligned} 5^1 &= 5 \ (\text{mod}\ p) \\ 5^2 &= 4 \ (\text{mod}\ p) \\ 5^3 &= 6 \ (\text{mod}\ p) \\ 5^5 &= 3 \ (\text{mod}\ p) \\ 5^{11} &= 3 \ (\text{mod}\ p) \\ 5^{17} &= 3 \ (\text{mod}\ p) \\ \end{aligned}\]As you can see we even used different exponents, but the results are the same. In fact, if the modulo is large enough, it becomes computationally infeasible to determine the original value from the encrypted value. And this “hard” problem is what is used in today’s cryptographic schemes to provide security.

All the homomorphic properties we discussed earlier still hold, but now the operations are performed modulo p.

Modular division is a bit more complex, as it requires the concept of modular inverses, which is out of scope for this post.

Side note: There are limitations to this homomorphic encryption scheme. While we can multiply an encrypted value by an unencrypted value, we cannot multiply two encrypted values together. This is because the result would not be in the form of $g^v$, which is required for decryption.

Here the proof: \(\begin{aligned} Enc(a) &= g^a \ (\text{mod}\ p) \\ Enc(b) &= g^b \ (\text{mod}\ p) \\ Enc(a) * Enc(b) &= g^a * g^b = g^{a+b} = Enc(a+b) \not = Enc(a*b) \ (\text{mod}\ p) \\ \end{aligned}\)

Encrypted polynomials

Next, that we have a homomorphic encryption scheme, we can use it to encrypt polynomials.

An encrypted polynomial is simply a polynomial where the coefficients are encrypted using our homomorphic encryption scheme. Let’s say we have the following polynomial:

\[p(x) = x^3 - 3x^2 + 2x\]We learned already, that to know a polynomial means to know its coefficients, here $1$, $-3$, and $2$. Because homomorphic encryption does not allow to exponentiate an encrypted value, we must be given encrypted values of powers of $x$ from $1$ to $3$:

\(Enc(x^1), Enc(x^2), Enc(x^3)\) so that we can evaluate the encrypted polynomial as follows:

\[\begin{aligned} E(x^3)^1 * E(x^2)^{-3} * E(x^1)^2 \\ (g^{x^3})^1 * (g^{x^2})^{-3} * (g^{x^1})^2 \\ g^{x^3} * g^{-3x^2} * g^{2x^1} \\ g^{x^3 - 3x^2 + 2x} \\ \end{aligned}\]The result of such operations is, we have an encrypted evaluation of our polynomial at some unknown x.

This is quite powerful mechanism. Let’s update our polynomial knowledge proof protocol to use encrypted polynomials.

- Verifier samples a random value $r$ which is secret

- Verifier calculates encryptions of $r$ for all powers from $1$ to $d$: $Enc(r^1), Enc(r^2), …, Enc(r^d)$ and sends them to the prover

- Verifier evaluates unencrypted target polynomial with $r$: $t = t(r)$ (Verifier knows $p(x) = t(x) * h(x)$)

- Verifier sends encrypted powers to the prover

- Prover calculates polynomial $h(x) = p(x) / t(x)$

- Prover evaluates $E(p(r))$ and $E(h(r))$ using encrypted powers received from the verifier

- The resulting encrypted values $E(p(r))$, $E(h(r))$ are provided to the verifier

- Verifier checks that $E(p(r)) = E(h(r))^{t(r)} = g^{t(r) * h(r)}$ and accepts the proof if the equality holds

Let’s see how this protocol works with $p(x) = x^3 − 3x^2 + 2x$ and $t(x) = (x - 1)(x - 2)$.

Setup

We know:

\[\begin{aligned} p(x) &= x^3 − 3x^2 + 2x \\ t(x) &= (x - 1)(x - 2) \\ h(x) &= \frac{p(x)}{t(x)} = x \\ \end{aligned}\]And we use: $g = 2$, $p = 101$ Therefore:

\[Enc(v) = 2^v \ (\text{mod}\ 101) \\\]Protocol Execution

- Verifier samples $s$ random value $7$

-

Verifier calculates encrypted powers:

\[\begin{aligned} Enc(7^1) = 2^7 \ = 27 \ (\text{mod}\ 101) \\ Enc(7^2) = 2^{49} \ = 50 \ (\text{mod}\ 101) \\ Enc(7^3) = 2^{343} \ = 86 \ (\text{mod}\ 101) \\ \end{aligned}\] - Verifier forwards encrypted powers to the prover

- Prover calculates $h(x) = p(x) / t(x) = x$

-

Prover evaluates encrypted polynomial $p(x)$ at $s = 7$ (prover does not know $s$ in cleartext :!:): \(\begin{aligned} E(p(7)) & = E(7^3 - 3*7^2 + 2*7^1) \\ & = E(7^3)^1 * E(7^2)^{-3} * E(7^1)^2 && \text{Prover received encrypted values } \\ & = 86^1 * 50^{-3} * 27^2 \\ & = 86 * 93 * 22 \\ & = 14 \ (\text{mod}\ 101) \\ \end{aligned}\)

Do not forget that:

\[\begin{aligned} E(a) * E(b) &= E(a + b) \ (\text{mod}\ p) \\ E(a)^k &= E(k * a) \ (\text{mod}\ p) \\ E(a)^{-1} &= E(-a) \ (\text{mod}\ p) \\ \end{aligned}\] -

Prover evaluates encrypted polynomial $h(x)$ at $s = 7$:

\[\begin{aligned} E(h(7)) & = E(7) \\ & = 27 \ (\text{mod}\ 101) \\ \end{aligned}\] - Prover sends $E(p(7)) = 14$ and $E(h(7)) = 27$ to the verifier

-

Verifier calculates $t(7) = (7 - 1)(7 - 2) = 30$ and checks that:

\[E(p(7)) \stackrel{?}{=} E(h(7))^{t(7)} = 27^{30} \equiv 14 \ (\text{mod}\ 101) \\\]

Since the equality holds, the verifier accepts the proof.

To explore the protocol’s limitations, let’s examine what happens when the prover attempts to cheat.

Cheating Prover Example

Setup remains the same, besides the prover using $p’(x)=t(x)*(x+5)$, which is divisible by $t(x)$ (so it has a clean cofactor). Steps 1 to 3 are the same as before.

- Cheating Prover uses $h’(x) = p’(x)/t(x) = x + 5$ instead of $h(x) = x$

-

Cheating Prover evaluates encrypted polynomial $p’(x) = x^3 + 2x^2 − 13x + 10$ at $r = 7$:

\[\begin{aligned} Enc(p'(r))=Enc(r^3)^1 * Enc(r^2)^2 * Enc(r)^{-13} * Enc(1)^{10} \equiv 87 \ (\text{mod}\ 101) \\ \end{aligned}\] -

Cheating Prover evaluates encrypted polynomial $h’(x)$ at $r = 7$:

\[\begin{aligned} h'(s)= s + 5 = 7 + 5 = 12 \Rightarrow E(h'(s))=E(s) * Enc(1)^5=27 \cdot 2^{5}=27 \cdot 32 \equiv 56 \ (\text{mod}\ 101). \end{aligned}\] - Cheating Prover sends $E(p’(7)) = 87$ and $E(h’(7)) = 56$ to the verifier

-

Verifier calculates $t(7) = (7 - 1)(7 - 2) = 30$ and checks that:

\[\begin{aligned} E(p'(7)) \stackrel{?}{=} E(h'(7))^{t(7)} (\text{mod}\ 101) \\ 87 \stackrel{?}{=} 56^{t(7)} (\text{mod}\ 101) \\ 87 \stackrel{?}{=} 56^{30} (\text{mod}\ 101) \\ 87 = 87 (\text{mod}\ 101) \end{aligned}\]

Since the equality does hold, the verifier accepts the proof.

That’s the whole point of the cheat: with a single hidden point $s$, the prover can pick a different polynomial $p’(x)$ (here still degree <= 3) that satisfies $p’(s) = t(s) * h’(s)$, where $h’(x)$ is the cofactor of $p’(x)$. The check passes at that point, even though $p’(x) \neq p(x)$.

Addressing the Issues

In the current protocol, we managed to address Issue 1 and Issue 2:

- Prover may not know the claimed polynomial $p(x)$ at all

- Now the prover cannot come up with any polynomial, since the verifier sends encrypted powers of a secret random value

- Prover can construct any polynomial which has one shared point at $s$ with $t(s) * h(s)$

- Now the prover cannot construct any polynomial, since the verifier sends encrypted powers of a secret random value

However, we still have Issue 3: No enforcement of degree.

- No enforcement of degree

- We still have no enforcement of degree. The prover can use a polynomial of higher degree which also satisfies the cofactors check.

Wow, that was a lot of information to digest. In the next section, we will address Issue 3 and complete our polynomial knowledge proof protocol.

Even with hidden evaluation points, our protocol still fails to restrict a prover’s polynomial degree. The next step introduces a mechanism to enforce this constraint-bringing us closer to real-world zkSNARK structure, where degree bounds are crucial for soundness.

Enforcing Polynomial Degree

Previously, we ensured that the prover couldn’t fabricate arbitrary encrypted values or match a different polynomial at a single secret point.

However, we still had no guarantee on polynomial degree - a malicious prover could use higher-degree terms while remaining undetected.

To fix this, we need a way to prove that the prover’s encrypted computations used only the encryptions of powers of the verifier’s secret value $s$.

Degree‑Bound Enforcement via the Knowledge‑of‑Exponent Assumption

Knowing a polynomial means knowing its coefficients. In our protocol, each coefficient corresponds to a power of the encrypted secret $s$. However, since the prover controls the exponentiation process, nothing prevents them from introducing extra terms unless we cryptographically bind every operation to the verifier’s provided values.

This binding is achieved through the Knowledge‑of‑Exponent Assumption (KEA), introduced by Ivan Damgård in Towards Practical Public Key Systems Secure Against Chosen Ciphertext Attacks.

The Knowledge of Exponent Assumption (KEA)

Let us understand first what KEA states before we integrate it into our protocol.

Knowledge of Exponent Assumption (KEA) is a cryptographic assumption that demonstrate the knowledge of an exponent in a given equation without revealing the exponent itself. KEA is often used in various cryptographic protocols to prove the possession of a private key without disclosing the private key itself.

In simple terms, if someone is given two group elements $g$ and $g^a$, and they later produce another pair $(X, Y)$ such that $Y = X^a$, KEA assumes they must actually know the number $x$ for which $X = g^x$.

They cannot simply “guess” or forge such matching values, producing a consistent pair implies knowledge of the hidden exponent.

Illustrative Example

To visualize how KEA works, consider a simple interaction between Alice and Bob:

Alice picks a random value $a$ that has to be exponentiated by Bob to any power, with the requirement that only $a$ can be exponentiated, and nothing else.

- Alice samples a random value $\alpha$

- Alice calculates $A = a^{\alpha} \mod n$

- Send $(a, A)$ to Bob

- Bob picks a random value $x$

- Bob calculates $X = a^{x} \mod n$ and $Y = A^{x} \mod n$

- Send $(X, Y)$ to Alice

- Alice checks that $Y \stackrel{?}{=} X^{\alpha} \mod n$

If the equality holds, Alice is convinced that Bob knows $x$ such that $X = a^x \mod n$. Alice hasn’t learned anything about $x$ itself, but she is convinced that Bob knows it. Bob also hasn’t learned anything about $\alpha$ - if he would, we would be in trouble.

Integrating KEA into Our Protocol

Setup

We know:

\[\begin{aligned} p(x) &= x^3 − 3x^2 + 2x \\ \end{aligned}\]And we use: $g = 2$, $p = 101, \alpha = 5$ Therefore:

\[Enc(v) = 2^v \ (\text{mod}\ 101) \\\]Protocol Execution

- Verifier samples $s$ random value $7$

-

Verifier calculates encrypted powers:

\[\begin{aligned} Enc(7^1) = 2^7 \ = 27 \ (\text{mod}\ 101) \\ Enc(7^2) = 2^{49} \ = 50 \ (\text{mod}\ 101) \\ Enc(7^3) = 2^{343} \ = 86 \ (\text{mod}\ 101) \\ \end{aligned}\]

and to enforce polynomial soundness under KEA, the verifier calculates also:

\[\begin{aligned} Enc(7^1)^\alpha = (2^7)^\alpha \ = (2^7)^5 \ = 2^{35}\ \ = 51(\text{mod}\ 101) \\ Enc(7^2)^\alpha = (2^{49})^\alpha \ = (2^{49})^5 \ = 2^{245} \ = 76 \ (\text{mod}\ 101) \\ Enc(7^3)^\alpha = (2^{343})^\alpha \ = (2^{343})^5 \ = 2^{1715} \ = 37 \ (\text{mod}\ 101) \\ \end{aligned}\]- Verifier forwards encrypted powers with and without the $\alpha$ shift to the prover

-

Prover evaluates encrypted polynomial $p(x)$ at $s = 7$ (prover does not know $s$ in cleartext :!:): \(\begin{aligned} E(p(7)) & = E(7^3 - 3*7^2 + 2*7^1) \\ & = E(7^3)^1 * E(7^2)^{-3} * E(7^1)^2 && \text{Prover received encrypted values } \\ & = 86^1 * 50^{-3} * 27^2 \\ & = 86 * 93 * 22 \\ & = 14 \ (\text{mod}\ 101) \\ \end{aligned}\)

and $\alpha*p(s)$:

\[\begin{aligned} E(p(7))^{\alpha} & = E(7^3 - 3*7^2 + 2*7^1)^{\alpha} \\ & = E(7^3)^{1*\alpha} * E(7^2)^{-3*\alpha} * E(7^1)^{2*\alpha} && \text{Prover received encrypted values } \\ & = (E(7^3)^{\alpha})^1 * (E(7^2)^{\alpha})^{-3} * (E(7^1)^{\alpha})^{2} \\ & = 37^1 * 76^{-3} * 51^2 \\ & = 37 * 64 * 76 \\ & = 87 \ (\text{mod}\ 101) \\ \end{aligned}\] - Prover sends $E(p(7)) = 14$ and $E(p(7))^{\alpha} = 87$ to the verifier

- Verifier checks $(g^p)^{\alpha} = E(p(7))^{\alpha}$ \(\begin{aligned} (g^p)^{\alpha} \stackrel{?}{=} E(p(7))^{\alpha} (\text{mod}\ 101) \\ (2^{p(s)})^{5} \stackrel{?}{=} 87 (\text{mod}\ 101) \\ (2^{p(7)})^{5} \stackrel{?}{=} 87 (\text{mod}\ 101) \\ (2^{p(7)})^{5} \stackrel{?}{=} 87 (\text{mod}\ 101) \\ (2^{210})^{5} \stackrel{?}{=} 87 (\text{mod}\ 101) \\ 2^{1050} \stackrel{?}{=} 87 (\text{mod}\ 101) \\ 87 = 87 (\text{mod}\ 101 \end{aligned}\)

With the added KEA check, we can be sure that the prover used only the provided polynomial by the verifier, and did not introduce any higher-degree terms, since there is no other way to preserve the $\alpha$-shifted relationship without knowing the exponents used.

The small-range problem

At this stage, our protocol works exactly as intended: the prover and verifier can both compute

\[(g^{p(7)})^{\alpha} = E(p(7))^{\alpha} \pmod{101},\]so the verifier is convinced that the prover knows the correct polynomial evaluation, without seeing the actual polynomial. That sounds like a zero‑knowledge proof, since nothing about the coefficients $c_i$ was revealed directly. But there’s a subtle weakness hiding here.

Zero-knowledge means the verifier should learn nothing about the hidden data, no matter what.

However, in this simplified modular example, our coefficients don’t live in a huge space, they take on small, easily enumerable values (for instance, between 0 and 100).

That small range opens the door for brute‑force attacks.

If the verifier knows the structure of the polynomial (say, $p(x)=c_2x^2 + c_1x + c_0$) and the evaluation point $x=7$, then they can simply try every possible combination of coefficients until their computed $E(p(7))$ matches the prover’s.

Even if each coefficient can take 100 values, a degree‑2 polynomial gives

$100^3 = 1 000 000$ possible combinations, something that a single modern computer can test in seconds.

Meaning of true zero‑knowledge

A truly secure zero‑knowledge proof would remain private even if:

- there were only one coefficient,

- its value were just 1, and

- the verifier had unlimited curiosity.

Summary

Our protocol illustrates the logic of zero-knowledge: how to prove a fact without revealing a value, but not the cryptographic strength of zero-knowledge, which depends on hardness assumptions rather than small parameter ranges.

In other words, the math works, but in a real system we’d need a much stronger secrecy foundation.